Because of his terror, intelligence, and ruthless efficiency, Pablo Escobar’s fortune was not only enormous but also deeply ingrained in international financial institutions. While Wall Street investors hailed the rise of blue-chip stocks in the 1980s and early 1990s, Escobar was actually hoarding cash. It was said that rodents eating through bundles of money cost his organization millions of dollars per year. His enterprise was remarkably successful and completely unreal, reaching heights that few legitimate companies ever attained.

Colombia was turned into a high-stakes narco-finance powerhouse by Escobar’s Medellín Cartel. He reorganized illicit trade with military-style discipline by controlling almost 80% of the cocaine supply in the United States. Every link was carefully controlled, from safehouses in Miami to secret airfields in Panama and coca plantations deep in the Andes. The cartel earned an estimated $420 million a week at its peak, which was a sum of money that was more than the GDP of some Latin American countries.

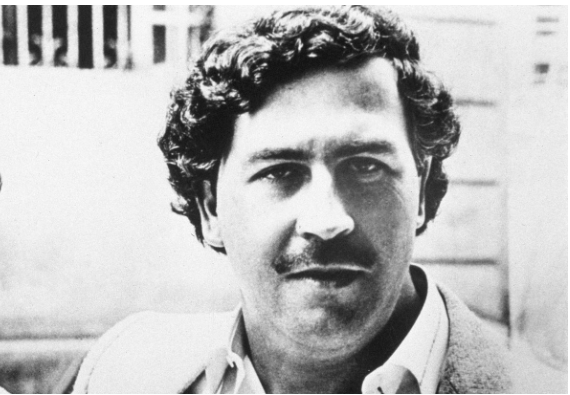

Pablo Escobar – Wealth, Power, and Influence

| Attribute | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria |

| Date of Birth / Death | December 1, 1949 – December 2, 1993 |

| Nationality | Colombian |

| Known As | The King of Cocaine |

| Peak Net Worth (1990s) | Estimated $30 billion (approx. $80 billion in 2025 adjusted value) |

| Criminal Role | Founder of the Medellín Cartel |

| Weekly Earnings | Estimated $420 million during peak operations |

| Major Estate | Hacienda Nápoles – Private zoo, airstrip, and sprawling compound |

| Foreign Properties | Mansions in Miami Beach, Isla Grande, Guatapé, Medellín, and others |

| Cultural Legacy | Inspired TV shows, books, merchandise, and Escobar Inc. (posthumous branding) |

| Reference Source |

He didn’t rely solely on force to succeed. Escobar was very inventive in his strategic use of political and financial power. He deliberately nurtured his reputation among Colombia’s poor because he recognized that perception frequently prevailed over the law. He was more than just a drug boss in the context of Medellín’s slums; he was also a benefactor. Families proudly hung his photographs in their living rooms, and children cheered when he came to visit.

Escobar acquired social armor by using altruism to leverage his profits. His influence is demonstrated by the fact that entire communities, such as Barrio Pablo Escobar, still bear his name. He constructed sports stadiums, provided funding for housing projects, and even provided meals to underserved populations. He blurred the distinction between hero and outlaw by being strategically generous.

However, hidden beneath that public image was unfathomable wealth, lavishly showcased throughout an asset portfolio. His crown gem was the 7,000-acre estate known as Hacienda Nápoles, which featured Spanish colonial homes, a runway, exotic animals, and a private zoo. It was essentially a billionaire’s Disneyland, constructed through trafficking rather than IPOs or technological advancement.

The estate’s reputation has significantly improved since it was converted into a theme park and nature preserve in recent years. Where hippos formerly roamed, families now have picnics. Near the intact gates that originally displayed his initials, schoolchildren pose. The change is symbolic, turning frightening places into places of learning and remembrance.

Escobar’s wealth was not limited to Colombia. In 1980, $765,500 was paid for his Miami Beach property, which had four bedrooms and direct access to the sea. It was a place of passage as well as refuge. It was eventually taken by the authorities, which was a tactical victory in a war against his covert network that was mainly losing.

Other sites provided both visual grandeur and guarded privacy, such as the Isla Grande compound in the Rosario Islands of Colombia. Parties, strategy meetings, and perhaps secret transactions that influenced hemispheric drug shipments were held at that estate, which is now tumbling under tropical overgrowth.

La Manuela, after his daughter, came next. The estate, which is located next to a lake in Guatapé, was attacked by competitors but is still a powerful representation of narco-wealth. The ruins, which once shone with polished stone and imported furnishings, are now littered with graffiti.

La Catedral, the opulent prison Escobar constructed for himself, was arguably the most amazing building. It had a dollhouse, a casino, a bar, and a jacuzzi. He had successfully secured a golden cage from which he continued to conduct business by negotiating the conditions of his imprisonment with the government. He escaped when Colombian authorities came in after he broke that agreement by killing competing comrades inside its walls.

Escobar managed an empire while living simply in flats in Medellín for years. He was eventually found and murdered in 1993. Although an era came to an end with his passing, his influence persisted.

Today, a new type of business is fueled by his name. In order to safeguard the family’s brand rights, Escobar Inc. was founded in 2014 and is run by his brother Roberto. The Escobar brand has been marketed through this company and is now printed on everything from tech devices to t-shirts. It’s considered tasteless by some, and commercialized by others.

Escobar’s tale is oddly similar to those of contemporary celebrity entrepreneurs. He combined charisma and danger, much like Richard Branson or Elon Musk. He did so illegally, unlike them. His brand endures, though. He has become oddly immortal thanks to National Geographic documentaries, Netflix’s Narcos, and countless memes.

In a contradictory move, society has accepted and exalted a guy who caused the instability of a whole country by incorporating his name into contemporary pop culture. The occurrence brings up moral dilemmas regarding story ownership. For what reason and by whom is Escobar’s narrative to be told?

Few people have had such scary financial influence. Despite being based on vice, Escobar’s wealth is comparable to that of oil tycoons or IT billionaires. His wealth, adjusted for inflation, is comparable to early-stage Bezos and exceeds that of media heavyweights like Ted Turner. His empire’s basis, not its size, is what sets him apart.

The fact that his cartel control approach has influenced successors is even more telling. For instance, Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán used remarkably identical strategies: segregated networks, centralized command, and widespread bribery. Even after Escobar’s death, the buildings he constructed have shown to be extraordinarily resilient.

Governments have been using more faster data analytics in recent years to break up drug networks, but cartels have adjusted. Modern traffickers employ cryptocurrencies and encrypted chat, whereas Escobar relied on coded ledgers and hidden runways. His blueprint is still fundamental, though.

His mythos persists in society as well. Whether he was a misunderstood genius or a monster is still up for debate among young Colombians. Influencers post selfies near his ruins, musicians mention him by name, and artists create murals. A larger social battle to strike a balance between justice and fascination is reflected in this dichotomy.

Despite being mostly confiscated or destroyed, Escobar’s fortune still causes financial and emotional repercussions. His stories are told to curious but conflicted tourists by tour operators. His tale serves as a legacy and a warning.