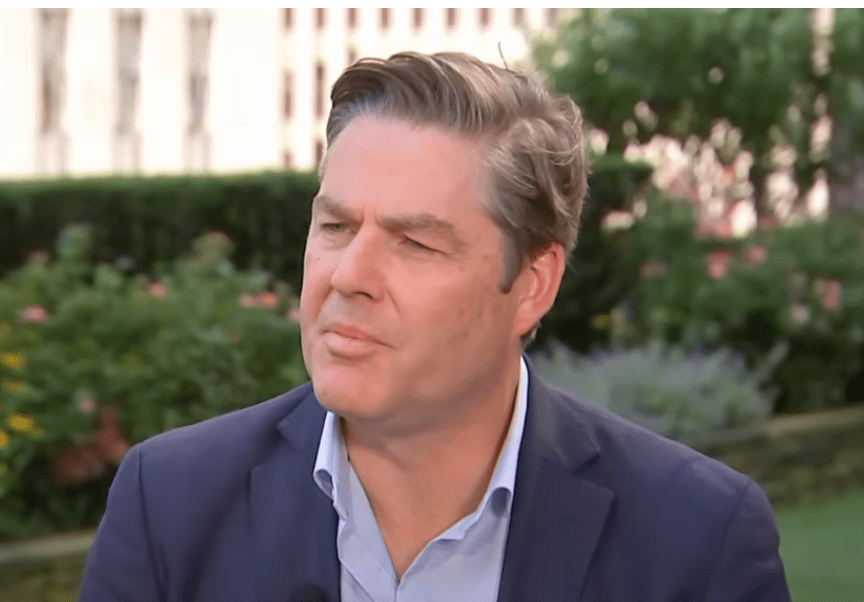

One of the most influential chairs in professional sports belongs to Richard Masters. His title as Premier League Chief Executive may conjure images of lavish bonuses, private planes, and corporate extravagance. Despite this, the amount associated with his name is remarkably low in public financial declarations. Masters is a non-executive director of Iomart Group PLC, and according to documents filed with the company, his total salary in 2021 was a meager £45,000. No pension, no equity, and no bonuses. The contrast is stark for someone in charge of a billion-pound ecosystem.

This amount, of course, simply represents his pay for that specific non-executive position. His true Premier League wage is still unknown. However, historical comparisons offer some insight. Before the structural split that put Masters in control, Richard Scudamore held the joint Executive Chairman position. It was believed that he made over £2 million a year, after incentives and benefits were taken into account. Neither stakeholders nor detractors would be surprised if Masters’ proposal fell into a similar bracket. The fact that his exact profits are unknown, however, surprises many.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Richard Masters |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Solihull School |

| Alma Mater | University College London |

| Current Role | Chief Executive, Premier League |

| Appointed | Interim (Dec 2018), Permanent (Nov 2019) |

| 2021 Public Salary | £45,000 as Non-Executive Director at Iomart Group PLC |

| Compensation Breakdown | £45,000 in cash, £0 in equity, £0 in pensions/bonuses (Iomart filing) |

| Notable Incident | Newcastle United takeover block, tribunal controversy |

| Club Politics | Influential roles by Liverpool and Manchester United during CEO recruitment |

| Current Chair | Alison Brittain (since July 2022) |

| Reference |

Since taking on the position full-time in November 2019, Masters has been negotiating incredibly turbulent conditions. Following an extremely lengthy selection process that included unsuccessful negotiations with three previous candidates, he was appointed. David Pemsel, Tim Davie, and Susanna Dinnage all died or disappeared. The public’s trust in Premier League leadership had significantly declined by the time Masters assumed charge.

Politics at the club level made things much more difficult. During the hiring process, Liverpool and Manchester United were accused of using backroom influence. These already disproportionately powerful clubs were suspected of holding informal screening sessions with shortlisted applicants, giving the impression that the Premier League’s wealthiest teams not only chose its leaders but also unofficially approved them.

After being verified, Masters was put in charge of operations during a period when the epidemic changed the face of football. A nearly insurmountable managerial conundrum was brought about by empty stadiums, declining match-day income, canceled games, and shaky broadcasting contracts. Under duress, he led talks with Sky and Amazon, assisted clubs in adapting to pandemic-era regulations, and made pronouncements that frequently raised more concerns than they answered.

In contrast, his public persona stayed surprisingly subdued. Although Scudamore enjoyed speaking in public, Masters has been remarkably silent, rarely participating in interviews or entering the fan-facing media arena. It appears that he would rather work behind the scenes.

His taciturn demeanor has not shielded him from criticism. Indeed, it became more intense amid the turmoil surrounding Newcastle United’s takeover. Newcastle formally accused the Premier League, and consequently Masters, of improperly thwarting a takeover attempt including the Public Investment Fund (PIF) of Saudi Arabia on September 9, 2020. The Premier League was accused of improperly applying the Owners’ and Directors’ Test after being improperly influenced, especially by the Qatari media outlet BeIN Sports.

During court cases, these charges intensified. Claims that the Premier League had “abused its position” when Masters was in charge were heard by a Competition Appeal Tribunal. The tribunal’s suggestion that external influence had distorted the process demonstrated how precarious league governance had become in light of geopolitically delicate situations.

The pressure only grew by 2023. The Saudi PIF was characterized as “a sovereign instrumentality” of the Saudi government by a U.S. court. Parliamentary scrutiny increased as PIF Governor and Newcastle chairman Yasir Al-Rumayyan was referred to as “a sitting minister” with sovereign immunity. MPs were looking for answers. Was this foreign ownership really unaffected by the government? Was the Premier League prepared, or even eager, to reconsider the agreement?

Masters’ answer was deliberately ambiguous. He asserted that he was unable to remark on the Newcastle-PIF connection’s legal standing or regulatory ramifications. That prudence seemed reasonable from a legal standpoint. Others saw it as a lost chance to demonstrate leadership in a changing ethical environment where transparency and sportswashing are more entwined than ever.

The paradox is that, despite being at the pinnacle of a worldwide athletic phenomenon with impact across continents, Richard Masters’ own position’s financial and ethical accounting is remarkably opaque. Should a person entrusted with such duties—juggling TV contracts, monitoring club ownership, and determining moral limits—have their pay concealed from the general public?

There is a growing trend in the sports sector toward increased transparency. The compensation of executives in racing, streaming services, and even public football teams has been analyzed and discussed. Masters’ cautious compensation plan seems more and more out of date in this light.

The strategic choices made by the Premier League have an impact well beyond the field. With billions of corporate dollars invested in its sponsorships and broadcasts, as well as millions of fans emotionally invested, its governance has a direct effect on public trust. Shouldn’t the chief executive’s performance be openly displayed if it is supported by risky diplomacy, media scheming, and moral judgment?

Some contend that keeping CEO compensation hidden from the general public prevents populist indignation. The counterargument, however, is stronger: responsibility is bred by transparency. The league runs the risk of being perceived as outdated—a closed-shop club protecting its own—without it.

The impact of football extends beyond the ninety minutes of play. It influences cultural perceptions, motivates large-scale movements, and, in the case of investments supported by Saudi Arabia, interacts with international diplomacy. Fans now want boardroom ethics to be as rigorous as VAR rulings.

The Masters’ journey is especially instructive because it reflects football’s overall trend, which includes enormous profits, skyrocketing stakeholder demands, and increasingly intricate relationships with international finance. Like many contemporary leaders, he functions more as a power broker than a typical CEO, negotiating a dynamic chessboard where every move is subject to public scrutiny.

Masters is a new type of sports administrator that is incredibly adaptable in handling emergencies but noticeably reticent when expressing long-term goals. It’s still up for dispute whether the Premier League needs that or if his subtle approach belies a higher level of strategic skill.